Here’s an excerpt from the chapter on growing and eating daylilies in The Lazy Gardener’s Guide to Easy Edibles:

Daylilies were introduced to American gardens in the late 1700s from Europe, where they had been brought from Asia in the Middle Ages. They are easily hybridized by transferring pollen from one flower to the stamen of another flower, and then growing out the resulting seeds. Thousands of varieties have been developed by this method.

True lilies—any plant from the genus Lilium—are toxic if consumed. Do not eat true lilies! Daylilies are not true lilies, but when eaten, they can cause allergic reactions in some people. If a person knows he or she is allergic to daylily pollen, they should avoid eating any part of the daylily plant.

One other word of warning about eating daylilies: all modern daylily cultivars are bred for the beauty of their flowers, not their edibility. For this reason, care should be taken when consuming newer cultivars. The older, naturalized species of daylily, such as Hemerocallis fulva (including the double orange blossom variety “Kwanzo”) and Hemerocallis lilioasphodelus L., the naturalized yellow daylily, are both tried and tested edible species. Most other varieties are probably edible—just be sure to eat a small portion of these other varieties at first to ensure that they don’t cause any adverse reaction. Some people experience an upset stomach after consuming large quantities of daylilies.

The daylily flowers, buds, and roots are all edible. Young shoots in spring are also edible and can be eaten raw or cooked in a skillet in butter. The flowers can be harvested, dried, and added to soups as a thickener. The flowers have a unique flavor and contain some protein and vitamins. They can be fried in batter using the tempura style of cooking.

How to Plant

Daylilies should be planted in a full-sun location with well-drained soil. The bulbous roots should be planted in loosened soil with the green leaves above ground. Water the new daylilies thoroughly after planting. Daylilies grow best with a least eight hours of direct sunlight each day.

Care

In much of North America, daylilies are delightfully easy to grow, as long as they receive adequate moisture and sunlight. Daylilies only need fertilizer sparingly, since over-fertilization will reduce blooming and may even kill the plant. Daylilies can benefit from an application of compost two to three times a year. If conventional fertilizer is used, apply a balanced fertilizer, such as 12-12-12, around the plants twice a year. Gardeners who grow daylilies for breeding or for show follow very specific fertilizer guidelines to ensure the plants produce the largest blooms.

Daylilies have a few pests, including aphids, spider mites, and thrips. When these pests are present in large numbers, they can be controlled using a homemade or store-bought insecticidal soap.

Very few diseases impact daylilies, and only one disease can kill them. Crown rot, a fungal disease caused by excessive moisture during the hot summer months, can kill daylily plants. If this disease and the conditions that bring it to daylilies persists in an area, it may be best to allow the planting site to remain free of daylilies for several years to help reduce the occurrence of this disease.

Once established, daylilies need to be watered only during dry spells. They benefit from a layer of mulch year-round.

Propagation

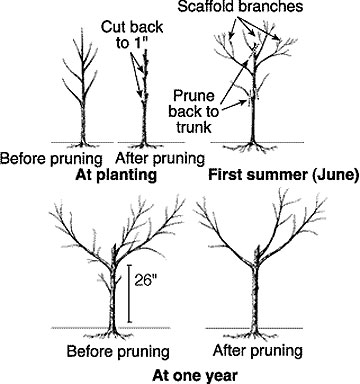

Daylilies are most commonly propagated by division, which involves dividing the clumps of daylily plants into smaller groups of plants. This is usually done in early spring before new growth has started. To divide daylilies, carefully dig up the existing group of plants, making sure to leave as much root mass intact as possible. Using a small spade or knife, divide the clump into individual plants or groups of two or three plants. These smaller groups of plants can be planted anywhere that is suitable for daylily cultivation.

Daylilies can also be propagated by seed. In some cases, bees and other insects will naturally pollinate daylily flowers, and seed pods will develop. Gardeners can also pollinate daylilies by moving pollen from one flower to the stamen of another. The resulting seeds will be a hybrid of the two parent daylilies.

Daylily seeds can be planted as soon as the seed pod is dry and open. They can be planted in pots or directly sown in the garden.

Container Growing

Daylilies are an easy plant to grow in containers. The daylily requires plenty of sun, and the plant may have to be divided frequently to keep it from outgrowing its container. Indoor container growing may not be practical because of the intense light requirements of the plant. Outdoor container growing is possible as long as the daylily plant is periodically divided or provided with a larger container as it grows.

Harvesting

For eating immature flowers, harvest the daylily flower buds right before they bloom. The entire flower can be harvested at peak bloom—usually the middle of the day—and added to soups. The young leaf shoots are best when harvested in the spring.

The roots (or tubers) can be harvested any time, though they are normally at their peak freshness from winter through early spring. Remove no more than 25 percent of the plant roots during this process to prevent injury to the plant. Select and remove the bulbous part of the roots. The small, fine roots are not edible.

Enjoying the Harvest

Besides its beauty, one of the joys of the daylily is that every part of the plant is edible at least part of the year.

Unopened flower buds can be cooked in butter and sprinkled with salt. Their flavor is rich and unique; it’s similar, though not identical, to that of green beans. Onions and herbs, such as tarragon and oregano, can be added for flavor. Daylily flower buds take about five minutes to sauté.

The opened flowers are mostly bland and were traditionally used to thicken soup and other dishes. They can also add color to a variety of dishes, including casseroles and salads.

The bulbous portion of the roots have a consistency similar to that of potatoes, but with a sweeter flavor. They can be eaten raw or cooked like potatoes. Remember to never eat a tuber that is soft—eat only firm tubers. Soft tubers are most likely rotten.

More info on this plant and 25+ other plants are available in this book: